Harry McClintock’s Big Rock Candy Mountain: A Whimsical Dream of Freedom and Escape

Share

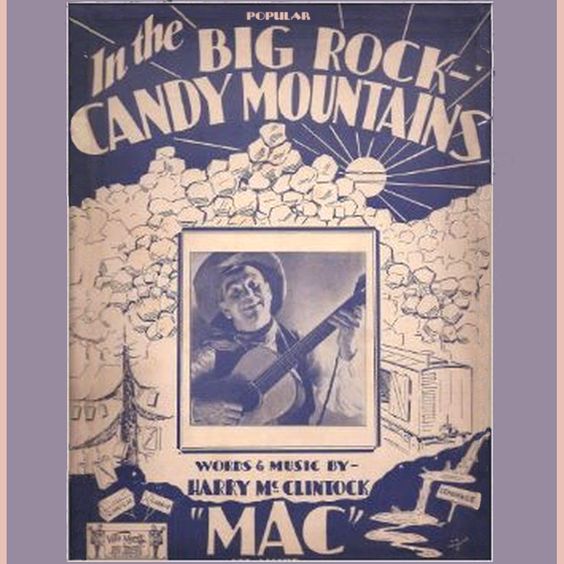

There’s something everlasting about a dream. No matter how absurd, how far away, or how unattainable, it holds power. In 1928, Harry McClintock, better known as “Haywire Mac,” first recorded and copyrighted Big Rock Candy Mountain, a whimsical ode to the kind of utopia only a hobo could imagine.

Haywire Mac wasn’t a musician plucked from privilege. He was a man of the rails, a drifter whose life was spent chasing work, adventure, and maybe, a little freedom. In the early 20th century, hobos like him were more than just wanderers; they were part of a unique subculture. They lived by a code, respected by their peers and wary of the world’s indifference. They weren’t today’s “bums.” They were travelers, workers, and dreamers—some of the only people willing to laugh at the absurdity of their circumstances and keep moving forward.

It was in this context that Big Rock Candy Mountain was born. Written during a time of incredible hardship, the song serves as both satire and sanctuary. It’s a utopian fantasy for the downtrodden—a place where work is outlawed, lakes flow with whiskey, and the very concept of suffering is replaced by carefree indulgence. Yet beneath its playful tone lies something deeper: a reflection of McClintock’s own life and the struggles of so many others. It’s a tribute to the resilience of hobos and, perhaps, even a glimpse of paradise

Decades later, Burl Ives would sing a softer, more polished version, reimagining the original irreverent utopia as something gentler, almost reverent. His rendition feels less like a hobo’s dream and more like a man’s wish, as though Ives was saying, “I hope McClintock found his Big Rock Candy Mountain.”

In this piece, we’ll not only explore the song’s lyrics but also dive into the life and times of Harry McClintock and the unique world of hobos in the early 20th century. This isn’t just an analysis of a whimsical tune; it’s a journey through a way of life that history often forgets—a time when a man with nothing could dream of everything.

Escaping Reality: A Dream Beyond the Rails

At first listen, Big Rock Candy Mountain might sound like a whimsical children’s song, but the lyrics hold more than playful absurdity. Each verse weaves a narrative of escape, indulgence, and defiance, painting a picture of utopia through the eyes of a man who has seen the world at its harshest.

“One evening as the sun went down / And the jungle fire was burning…”

The opening lines set the tone with a vivid scene straight out of hobo life. The "jungle fire" references the camps where hobos gathered, sharing food, stories, and dreams. The hobo in the song isn’t just walking—he’s on a mission, heading for a land of perfection, a place beyond the toil and struggle of everyday existence.

“On the birds and the bees and the cigarette trees / The lemonade springs where the bluebird sings…”

This iconic line epitomizes the whimsical nature of his fantasy. It’s not just about escaping hardship but about creating a world where even nature itself conspires to bring joy and abundance. It’s playful, absurd, and undeniably captivating.

“Where the handouts grow on bushes / And you sleep out every night…”

Poverty is flipped on its head. For a hobo, the idea of handouts being plentiful and sleeping outdoors becoming a choice rather than a necessity turns scarcity into abundance. It’s both humorous and poignant, reflecting a yearning for a life free from the indignities of poverty.

“All the cops have wooden legs / And the bulldogs all have rubber teeth…”

McClintock defangs authority and danger, turning what might have been a source of fear into harmless, almost comical figures. It’s an empowering image for anyone who has been oppressed or pursued.

“There’s a lake of stew and of whiskey, too / You can paddle all around ’em in a big canoe…”

As the song progresses, he leans further into indulgent fantasy, crafting a world of abundance and humorously exaggerated pleasures. Food and drink flow freely in this utopia, a stark contrast to the scarcity he and his peers endured. It’s so over-the-top that it becomes both hilarious and heartbreaking.

“The jails are made of tin / And you can walk right out again…”

Even imprisonment is inconsequential in this world. The systems meant to control or punish are rendered ineffective and temporary. For someone who faced the brutal realities of vagrancy laws, this is the ultimate dream of liberation.

“Where they hung the jerk that invented work…”

This biting satire is perhaps the song’s most famous line, and it encapsulates the defiance. For a man likely spending days chasing labor just to survive, this rejection of work is both ironic and deeply resonant. It critiques a system that demands endless toil while offering little in return.

The lyrics of Big Rock Candy Mountain are more than a whimsical story; they’re a blueprint for the perfect escape—a hobo’s utopia, his vision of paradise. Every hardship a hobo might face is transformed into absurd joy. It’s a fantasy steeped in humor, but also rooted in a sincere longing for freedom, safety, and abundance. In a time when survival often meant unceasing difficulty, McClintock’s vision of the Big Rock Candy Mountain was more than a dream—it was a lifeline of hope, humor, and resilience.

The Spirit of an Era: The Hobo’s Legacy

Harry McClintock’s Big Rock Candy Mountain is a reflection of an era, a way of life, and a mindset that embraced humor and absurdity as shields against an abrasive reality. For him, the hobo life wasn’t just survival; it was a unique form of rebellion, a rejection of a system that demanded constant struggle with little to show for it. Through his words, he built a world where hardship was flipped into joy, and everything oppressive was rendered powerless.

In many ways, the Big Rock Candy Mountain represents the ultimate utopia—not just for hobos, but for anyone longing for a place where suffering and fear dissolve into freedom and abundance. Its whimsical absurdity isn’t an escape from reality but a means of reimagining it, of laughing at its cruelties and dreaming of something better.

The song’s roots in hobo culture are unmistakable. Hobos of the time formed a subculture defined by resilience, independence, and a strict code of ethics. They weren’t aimless wanderers; they were workers, storytellers, and, in their own way, philosophers. They lived by a code that valued respect and dignity, even when the world offered them little in return.

To a modern audience, the idea of a “bum” operating with honor, respect, and a sense of community might seem foreign—almost mythological. Yet for hobos like McClintock, these values were not just ideals but necessary for survival and belonging in an often cruel world. This wasn’t a loose set of ideals—it was a deliberate framework for living. At the 1889 National Hobo Convention, a written code of ethics emphasized values like self-reliance, respect for others, and responsibility to the community. Hobos were encouraged to leave no trace, treat others—especially the vulnerable—with care, and always seek honest work where possible. They believed in helping their fellow travelers and holding each other accountable, even going so far as to hold “hobo courts” to address violations of their code.

Far from being a drain on society, hobos sought to contribute wherever they went. They carried themselves with dignity, priding themselves on cleanliness, resourcefulness, and mutual aid. In a world increasingly defined by individualism and disconnection, the hobo code’s emphasis on community, accountability, and mutual respect offers a perspective that feels both refreshing and timeless. These principles weren’t just about survival; they reflected an understanding of humanity. In a world that often dismissed them as outcasts, hobos forged a moral compass that, in many ways, feels aspirational today.

Decades later, Burl Ives would pick up where McClintock left off, reimagining Big Rock Candy Mountain in a way that softened its edges. Ives’s version isn’t just a beautifully polished rendition; it’s a heartfelt homage. Where the original laughed at the absurdity of his situation, Ives seemed to sing with a wistful hope, as if longing for McClintock’s dream to be real. His version feels less like satire and more like reverence, a quieter acknowledgment of the longing that runs beneath the humor.

Together, these two versions of the song tell a story of transformation. McClintock’s rugged humor and Ives’s wistful reflection show how art evolves with each interpretation, taking on new layers of meaning while retaining its core. Whether you hear it as a whimsical escape, a biting satire, or a heartfelt wish for paradise, Big Rock Candy Mountain remains a map to something universal—the human desire for freedom, safety, and joy.

But perhaps the most enduring legacy of Big Rock Candy Mountain is its ability to make us laugh and think at the same time. It’s a song that invites us to dream, to critique, and to imagine a world where the absurd becomes the ideal. And in doing so, it reminds us that even in the toughest times, we carry the power to envision something better.

For Harry McClintock, that vision was the Big Rock Candy Mountain. And maybe, just maybe, he found it.