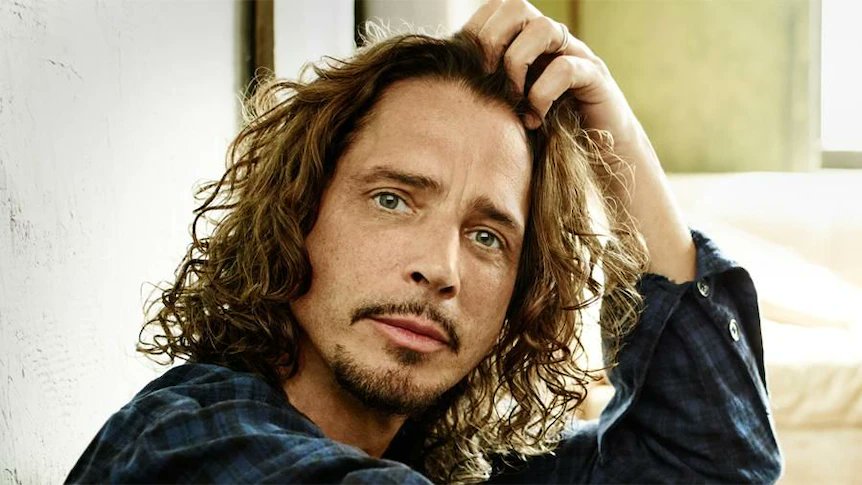

Audioslave’s Like a Stone: Chris Cornell’s Pain and Resignation

Share

"Like a Stone" by Audioslave is not just a sad song—it’s one of the most profoundly sad songs ever. From the very first note, it immerses you in a world of emotion and unshakable sorrow. Everything about it—the lyrics, the melody, the visceral delivery—forces you to confront the weight of regret and the loneliness of a man who believes he is beyond redemption.

At its core, this is the story of a man who is tormented by what he’s done. Whatever his sin, he believes it to be irredeemable. There is no arrogance here, no plea for forgiveness—just resignation. He has accepted his fate as one of eternal damnation. Alone, "like a stone," he will "wander on," endlessly waiting for salvation he knows will never come. This is not hope—it’s a quiet, devastating acceptance of his fate.

Chris Cornell’s voice tells a tale in itself. His delivery is more than a performance; it’s a confession. The pure anguish in his voice cannot be faked. It’s unrelenting, raw, and deeply personal. When he sings the final refrain of the chorus, his voice trembles under the weight of the song’s emotions. In that moment, he’s not just delivering the lyrics—he’s breaking, and you can feel every ounce of that pain. It’s this vulnerability, this undeniable grief, that transforms the song from a powerful piece of music into something unforgettable.

Cornell’s life only deepens the impact of Like a Stone. His struggles with depression and addiction were well-known, and his death—still surrounded by questions—left an indelible mark on the music world. While the lyrics themselves remain universal, they also feel intimate and introspective, as though they echo something Cornell was grappling with himself. The line between narrator and artist blurs, leaving us with a reflection of a man confronting forces larger than himself.

This is not an easy song to listen to—not if you’re paying attention. Its aching despair demands your full focus, forcing you to sit with the darkness that lingers in every note. But it’s in that pain where its beauty lies. As we explore its lyrics, we’ll walk through the story told in the artist’s own words—a story of regret, longing, and resignation. It’s the story of a man who waits, endlessly and alone, for a redemption he believes will never come.

At the Crossroads of Despair and Redemption

On a cobweb afternoon / In a room full of emptiness

The imagery here is stark and deliberate. A "cobweb afternoon" evokes a sense of stagnation, neglect, and time slipping away. It’s not just an idle moment but one where the narrator’s existence feels decayed, as though they’ve been left to wither in their isolation. The "room full of emptiness" mirrors their inner hollowness, suggesting that this desolation is not just external but deeply spiritual. It’s the kind of solitude that comes from a life weighed down by regret and the absence of grace.

By a freeway I confess

This line is incredibly layered. On one hand, the freeway could symbolize the chaos and perpetual motion of the world, contrasting sharply with the narrator’s stillness. They are confessing their sins in a world that refuses to slow down, emphasizing their alienation even further.

On the other hand, the freeway could be a reference to the infamous “crossroads” often associated with the music industry—a place where souls are said to be sold for worldly gain. In this context, the narrator’s confession becomes a moment of reckoning, an acknowledgment of the bargain they struck and the devastating consequences that followed. The crossroads metaphor adds a sinister dimension, implying the narrator willingly embraced this path, lured by false promises, only to discover too late that they had been deceived.

I was lost in the pages / Of a book full of death

Having been to the "freeway," the narrator turns to the Bible in search for answers that seem increasingly out of reach. The Bible is described as a "book full of death" both for its content and its implications. The Bible is steeped in stories of mortality, judgment, and sacrifice, and these themes confront the narrator with the stark reality of their own spiritual emptiness. The act of being "lost in the pages" suggests panic—a frantic search for answers, solace, or a path to redemption. Yet instead of comfort, they are met with the weight of judgment and the inevitability of death, reinforcing their belief that salvation is out of reach.

Reading how we’ll die alone / And if we’re good, we’ll lay to rest / Anywhere we want to go

This line underscores the intimate nature of faith and judgment: "we’ll die alone." The narrator recognizes that redemption is an individual journey, one that cannot be shared or borrowed.

The mention of being "good" and finding rest "anywhere we want to go" directly reflects the Bible’s promise of salvation for the righteous—a grace freely given but not guaranteed. For the narrator, this promise feels unattainable, as though it mocks them from a distance. This juxtaposition of hope and despair is key to the song’s power—it’s not about the possibility of salvation but about the crushing belief that the chance had already been forfeited.

False Grace and the Memory of Betrayal

“And on my deathbed I will pray / To the gods and the angels / Like a pagan to anyone/ Who will take me to heaven”

The narrator’s desperation in this moment is palpable. They are no longer tethered to faith, tradition, or even a coherent belief system. Instead, they are reaching out in a frantic grasp for salvation, willing to abandon all convictions in their final moments. This is not a prayer born of devotion or certainty—it is a plea from a soul untethered, willing to beg for mercy from any power that will listen.

The phrase “like a pagan” is particularly striking. It paints the image of someone disconnected from any specific faith, yet willing to try anything in their spiritual disarray. This act of prayer becomes less about faith and more about desperation—a raw, primal cry for grace, even as they feel unworthy of receiving it.

In these lines, we see a person utterly lost, flailing for redemption but without the conviction or hope to guide them. It’s a tragic reflection of spiritual collapse, where belief is replaced by bargaining and hope is overshadowed by guilt.

“To a place I recall / I was there so long ago”

This line introduces the powerful theme of memory and regret. The narrator recalls a place that once felt divine, safe, or fulfilling—a moment when they believed they were close to grace. It’s a longing for something they’ve lost, but this memory is shrouded in ambiguity and sorrow. Was it heaven? Innocence? A fleeting sense of spiritual connection? The vagueness of the “place” makes it universally relatable while deeply personal, allowing listeners to project their own experiences of loss onto it.

Yet, this memory is not one of comfort—it’s one of distortion. The narrator doesn’t just recall the place; they begin to recognize it for what it truly was. What once seemed holy becomes tainted, and the recollection shifts from longing to bitter realization.

“The sky was bruised / The wine was bled”

The imagery here is vivid and profoundly symbolic. The “bruised sky” evokes a corrupted or distorted version of heaven—a place that, on the surface, appeared divine but carried clear signs of violence and suffering. It’s a chilling reminder that not all light is holy, and not all beauty is pure.

The phrase “the wine was bled” is the most powerful metaphor of the song. It draws on the sacred imagery of communion, where wine symbolizes the blood of Christ, but here it’s desecrated and hollow. The act of grace has been drained, or bled, of its meaning, leaving behind only emptiness and betrayal. This is the moment where the narrator fully realizes the depth of the deception—that what they thought was heaven was, in fact, a carefully crafted lie.

“And there you led me on”

This line brings the verse to a devastating conclusion. It’s an acknowledgment of having been deceived, and an admission of their own role in following. The use of “you” adds weight—it’s accusatory but also resigned, as though the narrator recognizes both the manipulator and their own willingness to be manipulated.

The realization is crushing. They weren’t simply lost; they were led astray, lured by promises of grace that turned out to be false. This is not just a moment of treachery—it’s the bitter understanding that they walked into the deception, perhaps even willingly, only to be abandoned in their despair.

Trapped in the Shadows of Regret: A Fate Sealed by Guilt

“And on I read / Until the day was gone / And I sat in regret / Of all the things I’ve done”

The narrator’s return to the 'book full of death' reflects a cyclical, desperate search for redemption. The almost compulsive act represents their unrelenting search for meaning or redemption. Yet, rather than finding solace, they are left sitting in the suffocating weight of their regret.

The phrase “until the day was gone” symbolizes more than just the passage of a single day—it reflects the slow erosion of their life. Each moment slips away as they remain trapped in their guilt, unable to break free from the past. This stillness, this act of “sitting in regret,” reveals the narrator’s static, unchanging state. They are paralyzed by their failures, unable to move forward, consumed entirely by their inability to escape their own mind.

“For all that I’ve blessed / And all that I’ve wronged”

In this moment of reflection, the narrator acknowledges the totality of their life—every blessing they’ve bestowed and every wrong they’ve committed. It’s not a balanced scale but one irreparably tipped toward guilt. Even the blessings feel tainted, overshadowed by the magnitude of their mistakes.

This line captures the complexity of human morality: a life where good and bad coexist, yet the weight of regret drowns out any sense of redemption. For the narrator, it’s not just about what they’ve done—it’s about what they’ve failed to undo. This is the cruel paradox of their confession: the good feels insignificant, and the bad feels eternal.

“In dreams until my death / I will wander on”

And so, the narrator resigns themselves to eternal wandering. Even in dreams—the subconscious realm where escape might seem possible—they remain lost, plagued by their regret. The act of wandering signifies more than physical aimlessness; it is a spiritual exile, a perpetual fall from grace. This isn’t just a life lived in isolation—it’s a fate sealed by their own belief in their irredeemability.

The imagery suggests a haunting vision of eternal damnation, where the soul is forever adrift, unable to find peace or resolution. “Wandering on” becomes the ultimate punishment, a reminder of their separation from grace and a reflection of their internal torment. This is not just regret—it’s the complete absence of redemption, a punishment that transcends death.

The final image of wandering ties the verse together with devastating clarity. It’s not just a reflection on life—it’s a declaration of their eternal fate. Trapped in this cycle of regret and longing, the narrator envisions an unending disconnection from the grace they once sought, resigned to a fate of spiritual exile, forever adrift in their own damnation.

The Final Cry: A Longing That Breaks the Soul

“In your house, I long to be / Room by room, patiently / I’ll wait for you there / Like a stone / I’ll wait for you there / Alone / Alone”

The chorus is the emotional anchor of Like a Stone, and with each repetition, it grows in intensity and significance. It begins as a quiet profession—a yearning for grace, connection, or perhaps redemption. The narrator expresses a longing to be “in your house,” an evocative and ambiguous phrase that could signify heaven, peace, or even a return to innocence.

The imagery of “room by room, patiently” reflects a resigned kind of hope, a willingness to endure and wait forever. But it’s the phrase “like a stone” that captures the essence of this longing. The stone is lifeless, immovable, and unchanging, mirroring the narrator’s state of eternal waiting—static and alone.

By the final chorus, this refrain transcends its earlier iterations. Chris Cornell’s delivery shifts from quiet desperation to real, unrelenting emotion. His voice trembles under the weight of the words, carrying the full force of the narrator’s pain and resignation. It’s as if he’s no longer just singing but breaking, and in that breaking, the song reaches its emotional peak.

The repetition of “alone” in the final lines adds a crushing finality. It’s an acknowledgment of eternal separation from grace and connection. The narrator’s fate is sealed, and their isolation is complete.

The song's sentiments are visually echoed in the song's music video. It’s just the band performing the song to an empty room. Cornell begins seated, subdued, as though burdened by the weight of his own lyrics. As the verses unfold, he rises, his delivery reflecting the gradual intensification of emotion we hear in the music. His expressions vacillate between fleeting smiles and visible regret, mirroring the song’s delicate balance of yearning and despair. By the final chorus, the band unleashes, and the performance becomes a cathartic release—a visual counterpart to the song’s climactic culmination.

The brilliance of this chorus lies in its simplicity and progression. Each time it appears, it deepens the emotional resonance of the song, culminating in a final rendition that feels like an open wound. It’s a moment of pure catharsis, where the weight of the entire song crashes down in a devastating release.

A Redemption Beyond Reach: The Soul’s Eternal Question

Like a Stone is a confession, a lament, and a reckoning. It tells the story of a man who believes he is beyond redemption, resigned to eternal damnation, and trapped in a cycle of regret and longing. The song’s power lies in its ability to confront the rawest of human emotions—regret, guilt, and the unending yearning for grace—with devastating honesty.

Chris Cornell’s voice, trembling with sorrow and vulnerability, carries this weight as though it is his own. It’s impossible to separate the narrator’s journey from Cornell’s life—his struggles with depression, addiction, and the immense pressures of fame. His death, shrouded in mystery, echoes the themes of Like a Stone. Was this song his own self judgement? Was it a reflection of a man grappling with the weight of his choices, or was it something more universal, a mirror held up to all of us who have ever felt lost?

And yet, there’s another layer that cannot be ignored. The rumors surrounding Cornell’s life—the alleged work he was doing to expose child trafficking, the eerie similarities to the deaths of Chester Bennington and Avicii—add a chilling context. These artists, each known for their sincere sensitivity and emotional depth, seemed to be confronting darkness not just within themselves but in the world around them.

Cornell’s involvement in addressing trafficking speaks to a man seeking redemption—not from us, but perhaps from God. It reflects someone trying to tip the scales, even as he may have believed it was already too late. It’s this struggle that makes his music feel so deeply human, so painfully relatable.

Avicii’s For a Better Day delivers a vivid narrative about child trafficking, accompanied by a brilliant music video that exposes the exploitation and corruption lurking in the shadows. The song carries a message of justice and hope, yet its imagery and themes reveal the emotional and spiritual toll of confronting such unspeakable evils.

Similarly, Linkin Park’s What I’ve Done feels like a confessional—a raw admission of guilt and a desire to seek forgiveness for past actions. It reflects the artist’s deep engagement with themes of moral accountability and the struggle to reconcile with their own humanity.

Together, these works form a striking pattern: artists using their platforms to confront darkness, whether personal, societal, or both. Like a Stone may not answer the questions surrounding these tragedies, but it invites us to consider them. What might drive someone to feel irredeemable? To what depths must one descend to believe they are beyond grace?

But in the end, it’s not for us to determine whether Chris Cornell—or anyone else—is irredeemable. That is not our judgment to make; it lies between him and God. What we can do is bear witness to the profound humanity in his music. Like a Stone is not just a story of damnation—it is a story of longing for something greater, even when it feels unattainable.

The song’s final refrain lingers, both in its simplicity and its weight: “I’ll wait for you there, alone.” This is the essence of the song—a quiet, devastating solitude, and a willingness to wait for grace, even in the face of despair. It is a reminder that redemption, though it may seem out of reach, is not something we can measure. It’s a deeply human cry, one that leaves us both haunted and humbled.

Chris Cornell may have believed himself beyond salvation, but through his music, he leaves us with a question: is any soul truly lost? And perhaps the answer, like the song itself, is meant to be felt rather than known.